Ethereum will soon transition from a Proof of Work (PoW) to a Proof of Stake (PoS) consensus protocol. This transition has been worked on for years and is happening in multiple steps. The first step in December 2020 consisted in launching the beacon chain. It is now live, and, at the time of writing, has more than 160k validators or an equivalent of ~5m ETH staked on it.

The second step 'The Merge' may be happening in early 2022. While there are still many details beyond this step to be ironed out, enough has already been fixed about Pos Ethereum (eth2) for us to be able to reason about how Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) will look like in it.

In this post, we study transaction ordering in eth2 and analyze MEV-enabled staking yields. We find that MEV will significantly boost validator rewards but may reinforce inequalities among participants of eth2. We also discuss qualitative aspects of MEV in eth2 such as the potential dynamics that will unfold between its largest stakeholders like exchanges and validator pools.

Full analysis available here.

eth2 summary#

Ethereum's consensus is currently secured by miners who run hardware optimized to solve the proof of work challenge. The move from a PoW to a PoS consensus means the network becomes secured by validators, who stake security deposits of 32 ETH and vote to come to consensus on the state of the beacon chain. Validators are economically incentivized to do this via rewards for good behavior and penalties (slashing) for downtime or malicious behavior.

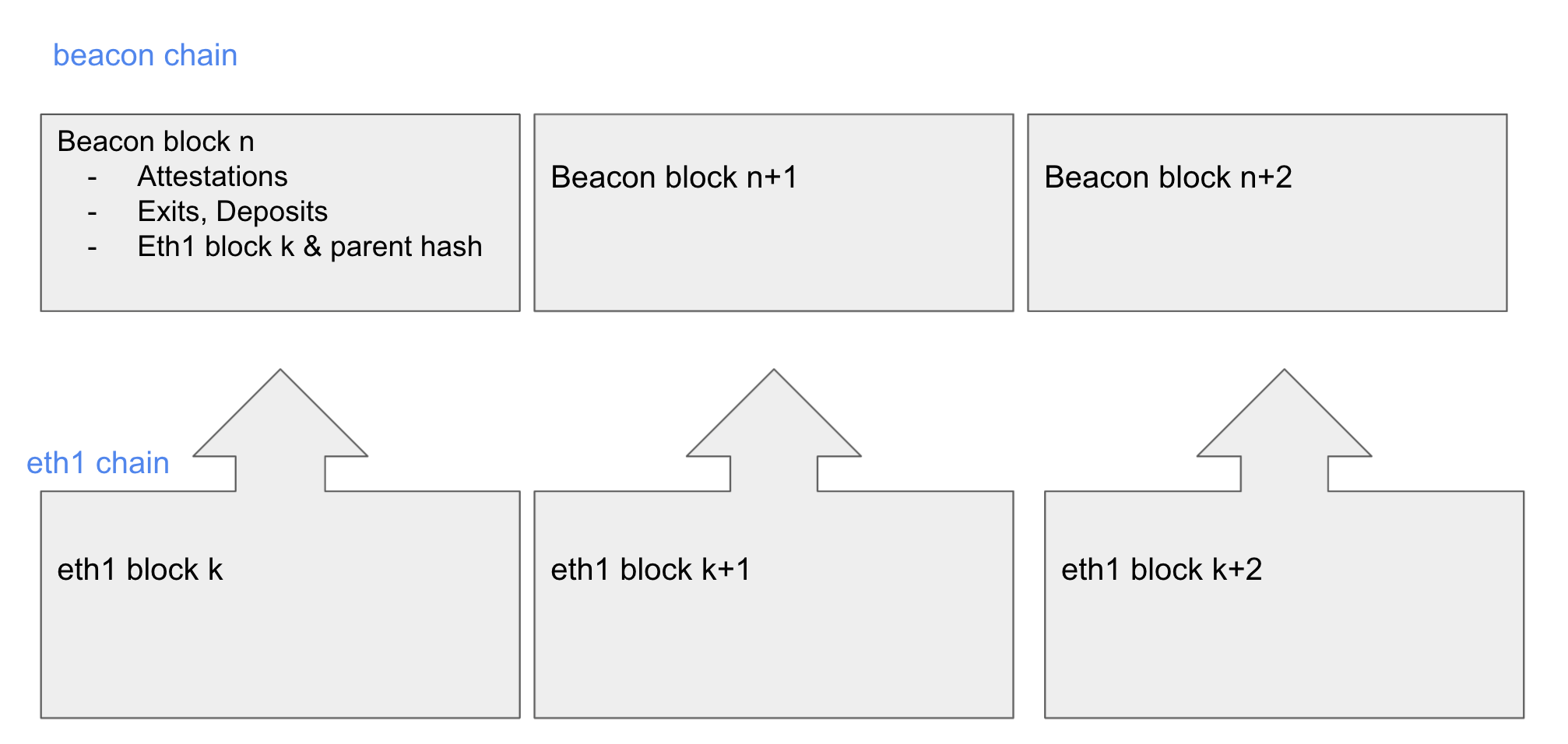

The beacon chain exists in parallel to the eth1 chain today and has been running successfully since December 2020. 'The Merge' entails - you guessed it - merging the beacon chain with the current eth1 chain. In the rest of this article, we'll use "eth1" to refer to Ethereum's execution engine with blocks and transactions as you know them today, "beacon chain" to refer to eth2's new underlying PoS consensus mechanism, and "eth2" as the post-merge canonical Ethereum blockchain which contains both the eth1 execution engine and the beacon chain for its consensus mechanism.

eth2 reaches consensus in 6.4 minute increments called epochs. Each epoch contains 32 slots, which are 12 seconds long, and each slot is a chance for a block to be added to the beacon chain. Under normal operating conditions, there will be 1 block per slot but causes like validator downtime can result in some slots having zero blocks.

For each epoch, all validators are pseudo-randomly assigned to propose blocks or attest to blocks proposed by other validators. These assignments are known 2 epochs in advance for attesters and 1 for proposers. The block in each slot will have a single validator serving as the proposer and many validators serving as the attesters to all information in that block, including data from eth1 and the beacon chain. Attesters get rewarded for accurately voting on current values of 3 aspects of the beacon chain: the head of the chain, the justified checkpoint and the finalized checkpoint.1

MEV in eth2#

MEV (Maximal Extractable Value) is all the possible value that can be reaped by a block proposer from the re-ordering, censorship or insertion of transactions within the block they are proposing2. In order to understand transaction ordering in eth2, we first focus on the inner workings of the software that will be used for it.

eth2 client#

As eth2 is essentially 2 chains merged together, it might come as no surprise that its client is composed of two sub-clients, one for the execution engine and one for consensus. Notably, current PoW Ethereum clients continue to exist in eth2 and are run alongside beacon clients, splitting responsibities between each other.

The eth1 client is a PoW Ethereum client stripped of its consensus responsibilities to focus solely on the eth1 tx pool, eth1 execution validity and the EVM. The beacon client on the other hand is responsible for consensus and validator duties (eg. beacon block attestation and proposal). They are run concurrently, each maintaining their own p2p networking stack (libp2p for beacon, devp2p for eth1).

An eth2 client may look like this modified diagram (taken from this article by Danny Ryan).

eth1 block proposal#

Just like it does today in PoW ethereum, the eth1 client in eth2 maintains a local mempool of transactions received from its p2p network. As described in Rayonism's spec, the beacon client interacts with it to form an eth1 block. While the communication channel detailed in the spec may change in production, the semantics of the methods will likely be preserved:

- Through several back and forths, the beacon client queries the eth1 client for an eth1 block it has formed from transactions received in its mempool, checking that it meets various validity conditions.

- Once the eth1 block is received by the beacon client, and has met the various validity checks, it is included by the proposer in the current beacon block and becomes part of the data attesters vote on.

- The beacon client then asks the eth1 client to update the head of its chain to the latest eth1 block that has been included.

- After a period of time, the epoch in which the beacon block is in is finalised and the beacon client notifies the eth1 client that the eth2 block has been finalized at the consensus layer.

While there are changes in how consensus is reached in eth2, transaction ordering within each eth1 block is the same as it is today, both in the software that orders transactions (eg. a Ethereum PoW client such as Geth) and in the p2p network transactions are gossiped through.

does MEV exist in eth2?#

Since the transaction ordering process in eth2 will be the same as that of PoW Ethereum, it is reasonable to think that MEV opportunities will still exist as we know them today. The difference lies in who has ultimate control over the ordering, namely validators rather than miners, who have been selected to propose a beacon block which will contain a fresh eth1 block they queried from the eth1 client.

This means a technology such as Flashbots' MEV-geth (a modified eth1 client software optimized for MEV extraction) that allows eth1 transaction senders to tip the block proposer (and transaction orderer) for their preferred ordering could still exist. Having established this claim, we can now think through how much validators stand to make from running software such as Flashbots'.

validator reward economics#

Pintail has recently released a detailed analysis of beacon chain validator rewards. We follow their approach (and re-use their code) in our own analysis which you can check out here and from which we've selected key takeaways below. We've also set up a live Binder for you to be able to play with the Python notebook in your browser directly.

While MEV is notoriously hard to measure, we use Flashbots data as a lower bound of the minimum additional revenue from MEV that block proposers stand to make. This is a lower bound because only a fraction of MEV activity is on Flashbots.

One caveat of this analysis is that it looks at MEV on top of protocol-mandated staking yields without including the transaction fees block proposers stand to make. The main reason for not including these is because it's hard to predict how much will be made from transaction fees post EIP-1559. This shouldn't be too bad of an assumption, since people not going for MEV will likely have little incentive to use more than the customary 1 gwei above the basefee however this does mean the relative impact of MEV on staking yields is overstated.

ideal case#

Let's consider first the case where all validators participate perfectly and get the maximum protocol reward possible (i.e. there is no slashing), and all rewards are distributed evenly since all validators stand to propose the same amount of blocks on an infinite timescale.

At the current level of validators (160k), we find that MEV can increase validator rewards by 75.3%, or give an APR of 12.86% rather than a non-MEV APR of 7.35% from staking eth. One takeaway from this is that higher validator rewards means more eth holders will be compelled to be validators which in turn means ethereum will be more secure by having a larger set of validators.

Looking forward to a near future where more validators come online, the boost to validator yields would be less significant, eg. 60% for 250k validators (8m eth staked). As mentioned above, this analysis doesn't factor transaction fees validators would make which would lower the relative impact of MEV on yields. Yet, these figures are still useful to compare to the additional reward miners are making from Flashbots today which sits at around 5.6%. This stark difference stems from the significant decrease in the rate of issuance in PoS. It suggests that MEV extraction will be a lot more desirable in eth2 than it is in eth1, and that there may be a big push from stakers to earn MEV-enabled staking yields.

factoring in time & REV distribution#

Over any finite timescale, there will be variability in validator rewards since there are specific protocol rewards for proposing blocks, and since some validators will be lucky and be given the opportunity to propose a greater than average number of blocks, and some unlucky, proposing fewer.

For example for 100,000 validators, the mean number of blocks proposed per validator per year is 26 yet the unluckiest 1% of validators will have the opportunity to propose at most 15 blocks, and the luckiest 1% at least 39.

Using this logic, we can plot the variability of rewards given those 3 different levels of block-proposal luck:

Now adding the average amount of Realized Extractable Value (REV) to miners per block recorded on Flashbots (0.185 eth) we can compare the 3 levels with and without MEV extraction:

The 3 levels without MEV extraction are now indistinguishable relative to the ones with it. This shows MEV extraction amplifies the inequality between validators that's created from block-proposal luck.

In addition, the distribution of REV is uneven and can be seen as a second dimension to luck, where some blocks will have a larger MEV reward than others. For instance here's the (long-tailed) distribution of Flashbots miner rewards in 100k recent consecutive Ethereum blocks starting with block 11600000.

We truncated the x-axis to 3 ETH for visibility, but the miner rewards in our sample go up to 101 ETH which you can find in our analysis linked above. Using this distribution of Flashbots miner rewards as a proxy for REV distribution, we can define and plot 3 levels of luck based on how much the unluckiest 1%, the median and the luckiest 1% validators stand to make from MEV rewards:

While the previous graph showed us MEV amplifies the inequality between validators created from block-proposal luck, this graph shows that the uneven distribution of REV is an even greater source of inequality between validators - especially considering the y axis goes to 600% here vs 80% in the previous plot.

In reality however, validators will smooth out the variance from block-proposal luck and REV distribution by pooling their resources in validator pools. While Ethereum PoS was designed such that validators get sizeable near constant rewards for valid attestations (as opposed to ~only when they propose a block like in PoW), the introduction of MEV in validator rewards could be a centralizing force by discouraging the operation of a solo validator and making it more financially attractive to join a pool for predictable and earlier liquidity.

Finally, we worry that MEV could amplify oligopolic dynamics in eth2 by enriching the entities with the most 32-eth stakes faster than the ones with less (rich-get-richer dynamics). This would make democratizing MEV extraction especially important in eth2 in order to preserve decentralization of consensus voting power.3

further analysis#

The Python notebook shared above details the rest of our analysis where we factor in slashing constraints in the model to study how penalties from lack of uptime and from validator participation rates are affected by MEV rewards. In the interest of brevity, we don't go over our results here but encourage you to check them out and contribute to them.

new consensus actors#

While the quantitative analysis above is important to start thinking about MEV in eth2, it is incomplete without a qualitative analysis of its actors. As previously outlined, hashrate leaves the stage for staked ETH in eth2. Miners and mining pools are replaced by new actors with control over large ETH holdings such as exchanges, protocol treasuries, investment funds and validator pools. This can already be seen to be the case looking at the existing distribution of eth1 deposit addresses in the current eth2 validator set on beaconcha.in.

It's important to note that this pie chart doesn't differentiate between the ultimate entity holding consensus voting power and the infrastructure it runs on. While consensus voting power centralization is concerning, infrastructure centralization is less so as PoS economic incentives encourage infrastructure decentralization to minimize correlated slashing risk.

Concretely, it means it's likely an exchange like Kraken with a large amount of eth would mitigate risks of slashing by distributing their stake across many infrastructure providers, running in different regions, on different hardware and using different clients rather than taking on that gigantic infrastructure task in-house.

exchanges#

The most notable shift in power dynamics in eth2 is the emergence of exchanges as the largest ETH holders and consequently the largest validators. Centralized businesses such as Coinbase, Binance and Kraken will likely control the largest amount of validator slots. These actors are regulated under different laws than mining pools and have many dimensions to their reputation. Such differences will likely exert new forces on the validator landscape relative to the miner landscape, and may shape the activities validators take part in such as the type of MEV they accept revenue from.

Interestingly, the fact these entities engage in several activities aside from staking may bring new opportunities for synergies between existing services these exchanges offer and MEV extraction. A few mentioned here include the ability to provide expedited transactions, private crypto withdrawals before they're included on-chain and reduced on-chain fees via what amounts to crypto-native payment for order flow.

Such service offerings may be cutting-edge at first and their benefits might mean users will migrate to exchanges that offer them, and consequently might hurt exchanges that don't or can't for regulatory reasons. In addition, the potential vertical integration of exchanges in the MEV game (eg. exchange running their own bots submitting txs to their own validators) is a point of concern we believe should be studied further.

validator pools#

Another important shift in eth2 is the rise of validator pools, providing benefits such as lowering the minimum eth needed to stake, spinning up validators for customers, smoothing out the variance from block-proposal luck (MEV + tx fees) and offering additional services such as staking derivatives thanks to the capital base they manage.

One interesting phenomenon is the emergence of meta-pools, like Rocketpool and Lido. These entities hook up to many validator pools and will likely be a large source of staking volume, and therefore be able to exert influence on the behavior of validator pools such as the type of MEV extraction they engage in and the profit-share they offer to stakers.

These meta-pools usually offer staking derivatives. An examples of such is the ability to offer users a liquid tokenized version of their staking deposit (which is normally locked) that they can use in the rest of the network. This would further compound the yield validators could make on top of MEV by allowing them to use liquid staked ETH back into DeFi.

Recalling the note above on infrastructure decentralization, one can see exchanges as another type of meta-pools, also hooking up to validator infrastructure on their backend. It's likely exchanges will also offer staking derivative services and that there will be competition between these traditional and native players that will play out on several dimensions such as decentralization, liquidity moats and regulatory flexibility.4

open questions#

Our exploration of MEV in eth2 has uncovered many open questions we're planning on researching in the next months. Below are four of them:

eth1 block proposer market#

As there are now in effect two clients to run (eth1+beacon), it's likely solo validators will choose to default their eth1 node to a service provider such as Infura as the overhead of running it themselves is significant. This could hint at the beginning of a separation between eth1 and eth2 node runners. Assuming such a dynamic unfolds, one could imagine a marketplace of eth1 node runners running high-performance hardware and MEV simulation software, catering to eth2 block proposers.

new constraints to mev search optimization#

MEV opportunities such as price arbitrages and liquidations still exist in eth2 but the system in which their extraction takes place possesses new parameters which may modify, or introduce, constraints to MEV extraction.

Block times are now fixed at 12 seconds, rather than variable block times in eth1, and proposer slots are assigned at the beginning of each epoch which means proposers would have at most 6.4 mins to compute their assignment (with proposers assigned at the beginning of the epoch having strictly less than that)5. This not only potentially gives more time for validators to run computing jobs for optimal MEV extraction on the eth1 client mempool, but also makes simulation and execution easier because of the predictability of block times.

This points to potentially more sophisticated compute-heavy MEV extraction enabled by a longer, and more predictable, time interval to compute and execute MEV extraction strategies.

changes in leader selection mechanism#

Validators will know ahead of time whether they get to propose a block (unless they are first slot of new epoch). They could even (albeit low probability) be the proposer of mutiple blocks within one epoch. How does the guarantee of being a block proposer change the dynamics of MEV extraction? What about the guarantee of being a multi-block proposer or contiguous multi-block proposer?

In particular, large validator pools/exchange will be the most likely to hold multiple contiguous slots within the same epoch. This could enable multi-block MEV extraction by creating a meta-slot out of the number of continuous slots held by a single entity, and might open up new vectors of attacks. 6 7

layer 2s & sharding#

Most of this post assumes that the content of eth1 blocks content will remain what it is today. In reality however, a lot of transaction flow will be ported to Layer 2s, and the layer 1 will be used as a data availability layer where zk-rollups and optimistic rollup batches of ordered transactions will be submitted.

This would intuitively lower the amount validators would stand to make from MEV. Yet, it is hard to predict as the multi-l2 world brings in additional complexity that might open up new forms of MEV (i.e. cross-L2, L1-L2). In addition, in a world of cross-L2 interactions there may still be an importance to the ordering of batches within eth1.

Similarly, as eth2 continues to develop and sharding goes into production, there may be significance to the order of shards within beacon blocks and MEV might become an incentive mechanism to facilitate shard staggering.8

Join us!#

Our exploration of MEV in eth2 has raised more questions than it has answered and we look forward to researching those further amongst the community to understand it.

We've already shared some our findings in talks here and here, as well as worked on an early prototype of an MEV-enabled eth2 client at ETHGlobal's Rayonism hackathon in partnership with Lido and Nethermind.

At Flashbots, we perform research and build systems around MEV, and we would love your help. We are a distributed organization with the principles of a pirate hacker collective, and have several open positions. We also issue grants to external researchers doing work aligned with ours, please find out more in our Research repository, or join our Discord!

Thanks to Terence Tsao, Raul Jordan, [Alejo Salles](https://twitter.com/fiiiu), Luke Youngblood, Tomasz Stanczak, Lakshman Sankar, Barnabe Monnot, Caspar S, and Viktor Bunin for their valuable contributions and edits to this post. And thanks to the rest of the Flashbots team for discussions leading to it._

- More on justification and finalization https://our.status.im/two-point-oh-justification-and-finalization/↩

- MEV is a metric representing the total value that can be extracted permissionlessly from the re-ordering, inclusion or censoring of transactions within a block being produced on a blockchain. So far, MEV extraction on Ethereum has been primarily conducted by DeFi traders and bot operators via the execution of trading strategies where transaction ordering matters, with a small percentage going to miners from the gas fees associated with these actors’ MEV transactions. Read more about MEV here↩

- a topic discussed by Phil Daian in MEV...wat do.↩

- More on staking pools and staking derivatives in this great post↩

- https://benjaminion.xyz/eth2-annotated-spec/phase0/beacon-chain/#compute_proposer_index↩

- If a pool holds out of total validators, the probability of producing an individual slot is . The probability of the pool producing two consecutive slots within an epoch is . (The probability of producing 2 consecutive slots when relaxing the single-epoch constraint is actually slightly higher considering that now unique validators could produce adjacent slots across epochs---a tiny effect for the larger numbers we're interested in here). If we take the approximate numbers of total validators, and the largest pool (Kraken) running of them, we find and , or .↩

- In addition, there are concerns outlined by Vitalik Buterin of randomness manipulation from controlling contiguous slots of the end of an epoch.↩

- More on incentivizing shard staggering here by Vitalik Buterin↩